Když babička Paquita odešla po 12 dnech v nemocnici domů, byla stupnice tragédie zachycena v jediné poznámce na propouštěcí zprávě: „Pokud se její stav zhorší, nevracejte ji zpět.“

Dvanáct dní předtím byla 89letá Paquita plná života a lásky, jichž bylo hodně. Jejích šest dětí jí požehnalo 11 vnoučat a pět vnoučat. Oni a všichni v její vesnici v provincii Málaga na jihu Španělska znali její laskavé srdce a to, že v jejím těle nebyla škodlivá kost.

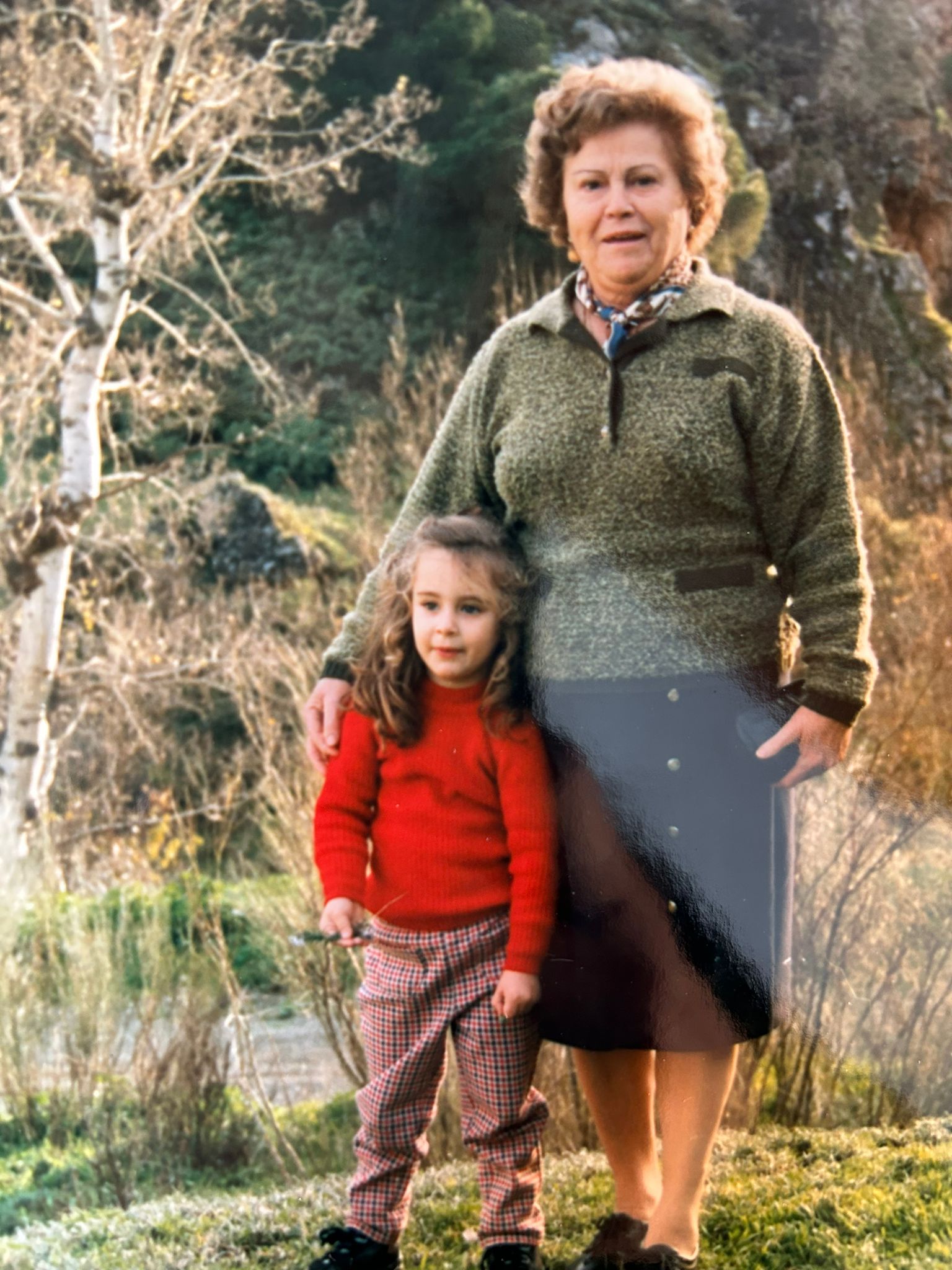

Babička Paquita byla pro Alicii Arjonu, poradkyni pro Andalusii, jejím vlastním andělem.

„Je to ta nejlepší osoba, kterou znám,“ říká Alicia, „a pro mě je to moje druhá máma. Vždycky to byla má matka, babička a já – od dětství. Byli jsme super blízcí, jen my tři.“

O několik týdnů dříve slavila rozšířená rodina své 89. narozeniny radostnou hostinou, kterou Paquita pomohla připravit. Kromě toho, že to byl důvod k oslavě, 89 bylo jen číslo, které Paquita vzdálila díky své nezávislosti, energii a mladistvému duchu.

Ale po mozkové cévní mozkové příhodě přerušilo zásobování malé, ale životně důležité části mozku, se číslo 89 stalo bouchajícím blokem, což je datový bod, který informoval o kritickém rozhodnutí, a poté se vše stále zhoršovalo.

Noční můra se rozvine

Ačkoliv byla sobota, Alicia byla v práci, když jí její matka Josefa volala, aby řekla, že babička Paquita měla cévní mozkovou příhodu. „Můj svět začal havarovat,“ vzpomíná. A co je ještě horší, nemocnice, ve které byla Paquita přijata, i když byla nominálně připravena na cévní mozkovou příhodu, odmítla spolupracovat s Angelsem na zlepšení péče o cévní mozkovou příhodu. Koordinátor cévní mozkové příhody opakovaně rebazoval Aliciiny nabídky, aby jim pomohl optimalizovat jejich hyperakutní cestu; sestry neměly zájem o zvýšení standardu postakutní péče.

Několik dní Alicia posedle vyšetřovala jejich rozhodnutí neléčit babičku trombolýzou z důvodů, že užívala antikoagulancia, na která nebyla žádná antidota. Říká: „Byla jsem spotřebovaná možností, že se k ní neléčili kvůli jejímu věku.“

Pro rodinu babičky Paquity se mezitím rozvíjela postakutní noční můra.

Protože se neočekávalo, že Paquita přežije cévní mozkovou příhodu, byla přeložena na interní oddělení, kde ji mohla obklopovat rodina. Podle lékařů by to byla otázka hodin.

Když se Paquita tvrdohlavě přilnula k životu, Alicia očekávala, že bude přemístěna do jednotky, kde by odborná ošetřovatelská péče mohla zmírnit dopad náhlé mozkové příhody a zabránit komplikacím. Lůžka s cévní mozkovou příhodou však byla vyhrazena pro mladší pacienty a pro ty, kteří podstoupili rekanalizaci a babička Paquita byla 89 let.

Děláme, co je třeba

Na interním oddělení, kde Paquita nyní leží, nebyl k dispozici protokol FeSS ke sledování horečky, cukru a polykání, bez neurologického vyšetření, bez pozornosti k úhlu lůžka, bez protidestičkových léků k prevenci druhé cévní mozkové příhody, bez ostražitosti ohledně krevního tlaku pacienta. Neschopnost přesvědčit zaměstnance, aby odcházeli z práce jako obvykle, stále více franticí Alicia zavedla první pravidlo Andělů: udělala vše, co bylo v jejích silách, aby dala babičce šanci.

Během následujících 10 dnů vytvořili Alicia a Cristina, mladá sestřenice, která se nedávno stala zdravotní sestrou, virtuální cévní mozkovou jednotku kolem postele své babičky. Alicia ukázala správné postupy a kontrolní seznamy na stěně a na překládacím stole. Načetla si glukometr, který používala pro simulační trénink, a poučila Cristinu, aby sledovala Paquitinu glukózu v krvi každé čtyři hodiny. Zuřivě přerušila zdravotní sestru, která do úst své babičky vlékala komerční želé a šla do lékárny, aby si koupila zahušťovadlo pro test dysfagie. Poté, co jim člen anadalského řídícího výboru zdravotních sester pomohl provést teledysfagický screening, Alicia vysvětlila, že Paquita potřebuje krmivo pro zbytek rodiny.

Šílenství a smutek

Pokud by zdravotní sestry na oddělení Aliciiny zásahy nepřivítaly, jednoduše by jí to nezajímalo. Když trvali na tom, že nikdy neměli případ ambiciózní penutonie v důsledku dysfagie, prohlásila, že její babička nebude první. Když lékařka navrhla, že by bylo nejlepší se pustit, vyřešila, že by to nebylo v důsledku podání vody, kterou nemohla spolknout.

„Moje babička trpěla,“ říká. „Nenechtěl jsem jim dovolit, aby udělali něco, jen aby se vyhnuli boji.“

Bylo jí šílené i smutné, že její babička mohla být léčena jinak, pokud nebyla na její věk. „Právě viděli jiné staré tělo,“ říká Alicia. „To byla ta nejbolestivější věc.“

Ale měla přicházet větší bolest.

Dne 12. června, dva dny po přijetí do nemocnice, vykazovala Paquita stejné příznaky jako při cévní mozkové příhodě. Nebylo však provedeno neurologické vyšetření a nebylo objednáno CT vyšetření. Místo toho dostala léky na úlevu od nevolnosti. O pět dní později se stejné příznaky znovu objevily. Byla sobota a lékař tentokrát neodpověděl na telefonáty.

V den propuštění 22. června CT potvrdilo heamoragickou transformaci a sekundární cévní mozkovou příhodu v jiné části mozku. Škoda byla obrovská.

Poté byla do formuláře propuštění přidána poznámka: „Pokud se její stav zhorší, nevracejte ji zpět.“

Stříbrná podšívka.

Josefa a Alicia stále navštěvují Paquitin domov, ale sotva ví, kde je nebo kdo jsou. Ačkoliv zatím přežívá, Josefa už ztratila matku a Alicia ztratila anděla. Říká: „Už není moje babička.“

Alicia se rozhodla najít stříbrnou výstelku a zmínila svou vděčnost andělské komunitě ve Španělsku, která ji po celou dobu obchodu držela v srdci a rukách. A nikdy nebyla více přesvědčena o potřebě Andělů: „Nyní mám další příklad, jak křehké jsou životy pacientů s mrtvicí a jak důležitá je naše práce, která jim pomáhá.“

Lékaři a zdravotní sestry v nemocnici neviděli poslední vnučku Paquity. Říká: „Chci, aby tato nemocnice byla vyškolena tak, aby nikdo netrpěl stejným způsobem. Budou se muset připojit k síti telemrtvice a řídicí komisi a budou muset souhlasit s prací s Angels na jejich protokolu a cestě.“

Doufá, že dokáže využít jejich empatii tím, že je povzbudí, aby si představili sami sebe v roli rodiny pacienta s cévní mozkovou příhodou. Doufá, že je přesvědčí, že je jejich spojenec a že jejím záměrem je pomoci jim zlepšit se v tom, co dělají. Nemá v úmyslu je vybrat.

Říká: „Nebudou schopni říci ne.“